Audio:

There comes a time when everyone can look at their life with some distance and see how it has turned out so far. For some, it’s when a significant birthday is on the horizon, when context and objectivity can be separated from emotion and attachment.

A matter of months before Tony Lloyd from Shropshire would turn 50, was the perfect time for him to take a look at the 45 years that had passed since he first picked up a golf club with his father Clive. For most kids, at that age, Dad’s clubs are always way too long, but for Tony, they fitted neatly and were just the right size. You see, Tony has a condition called phocomelia, which in layman’s terms means short limbs. Tony has short arms, “It’s just a genetic twist of fate, I guess. It just meant my arms didn’t develop completely. They basically end at just about the elbow on both hands. I’ve got a digit on one side which I call my thumb, and then I’ve got two fingers on the other side. So, obviously, no hands is another thing, never mind the short arms.”

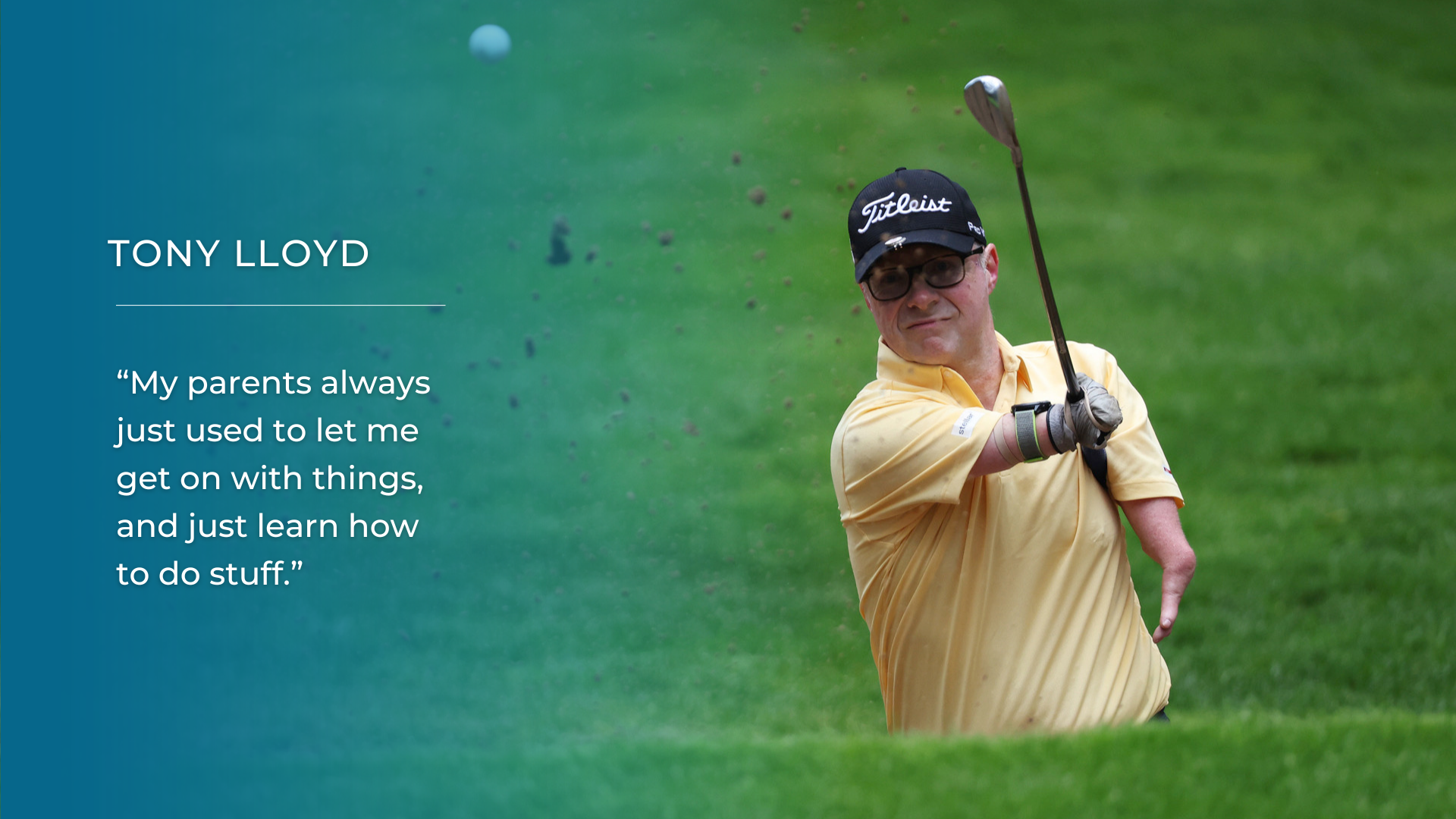

Tony learned to do all the ordinary things with what he has, although shoelaces, ties and top buttons present a challenge. Tony has learned to do everything in his own way, “My parents always just used to let me get on with things and just learn how to do stuff,” and swinging a golf club was no different, as the five-year-old Tony pulled a club from his father’s golf bag. “One day we were at the local driving range, and he was hitting golf balls, and I think I just literally pulled a golf club out of his bag and naturally put it under my arm like I still swing now. I could use his clubs quite comfortably, but I soon grew out of them.”

Golf would soon fade into the background as Tony grew and the clubs became too short for his unusual way of holding them, that is until he was paying a final visit to the limb centre in Roehampton, London. His regular therapist was away, but this chance meeting would change Tony’s life. “I was 18 or 19 years old, and the therapist said, ‘Look, we’ve not been able to help you with anything else, so we probably don’t need to see you again, but is there anything that you can think of that you can’t do which you wish you could?'” Almost mischievously Tony said he would like to play golf! This was the right question, at the right time, to the right person. The therapist was a golfer and took on the challenge to get Tony swinging a club and even snapped the head off his own three iron and welded it to a piece of copper pipe. In his enthusiasm, he neglected to wrap any kind of grip on the club before passing it to Tony and saying, “Here try that.” Moments later, Tony was swinging the homemade club, “And do you know, it actually worked. I mean, it ripped my armpit to pieces, but it suddenly made me think, wow, this is something I could actually do.”

A door had been opened, and Tony was keen to step through it. Although the journey from those few swings with a copper piped three iron to his current 8.8 golf handicap has been long, it has been full of people who have stepped in to help and some magical moments have been forever woven into Tony’s life story. Everyone has to find their own way, although for many, observing tried and trusted ways to do almost anything is how we learn. For Tony, role models are few and far between, and so experimentation, reflection and adaption are commonly the best way for him to make progress. “I was spotted by the local golf pro Dave Kelly at the range, and he thought of the idea of maybe getting a driver shaft and putting another one into the end of it. That was much better, with a proper grip on it, way better than a copper pipe ripping my armpit apart. I could practise properly, and I actually did nine holes.” The new club really lit a fire in Tony as he thought that golf was something he could pursue. “I was put in touch with Anne, who had her own golf business, by a colleague at the Lloyds Bank where I worked. Personal Touch Golf in Stafford didn’t just make me a couple of clubs, they actually put 10 clubs together for me.”

By now Tony was enjoying the recreational side of the game, “I was able to play with some of my friends who played golf. I was only ever playing a couple of times a year, but I was actually able to go out, and it was just something that was bubbling along.” Another breakthrough came with the Two-Thumb grip, which originally was designed by Philip Gazeley for putters. His design along with the Fatso and more recently the Super Stroke grips opened yet another door for Tony, who again embraced the opportunity. “When I started playing, I could only ever play one round then I’d need time for my armpit to heal. Obviously, holding the club under my armpit as I do, meant that I used to get friction burns. Even on a summer’s day, I’d go out with layers of clothes on, and I was sweating bullets. At least I could get around, but at the end of it I was really, really sore and it would take several days to heal. We put the Two-Thumb grips on, and I took one home to try and my goodness. I played 18 holes and then went to the range for an hour afterwards. Quickly we put Two-Thumbs on everything.”

While Tony was learning to play there was no book available on how to play golf with phocomelia, and so he had to figure it out with the help of more enlightened PGA professionals who would take the time to understand his needs. “A lot of them who tried to coach me and also tried using my clubs so they could get an idea of how to help. But I suppose the biggest influence is seeing another person with phocomelia. When I saw Richard Saunders for the first time it was striking really, because it’s the first time I’ve ever seen another person hit the golf ball like I do. It was a bit of a shock. I just thought, ‘Wow, is that what I look like when I swing a golf club?’ Now I see more and more short-armed golfers like myself, and I can see something in their swing that I can use and learn from.”

Golfers of all abilities can play together, and 90% of Tony’s golf is played as a regular player with the other members. As time ticked along, Tony developed his game at the local club Horsehay Village Golf Club oblivious to the opportunities that lay in golf for the disabled. Then in 2005, the idiosyncratic words of BBC commentator Peter Alliss stopped Tony in his tracks, with the realisation that there were events specifically for golfers with a disability and that they all played together. Yet another door had been opened, and once again Tony strode through it. He did not know what to expect but was open to the possibilities.

The ever-increasing visibility that golf for the disabled is achieving helps in ways that could never before have been imagined. “Professionals see me play and then invite me down so they can work with me. So, I’ve worked with Mark Roe, he’s a commentator now but former European Tour winner. And Andrew Murray, former European Open winner.” One unforgettable moment was when Tony was invited to hit balls on the range during the European Tour British Masters by former Tour player and Sky Sports commentator Nick Dougherty. Surrounded by Ryder Cup players, tournament winners and some of the very best professionals in the world, Tony stepped onto the range with some trepidation to take his place live in front of the cameras and hundreds of thousands of viewers around the globe. “Inside I was just looking around thinking, my goodness, I’m on a range here with these guys. I don’t think it’s an arrogant thing to say, but when I was hitting golf balls I was doing what I like doing, and because it’s a real passion of mine I was in the comfort zone to a certain extent. Even so, once they took the microphone off, there was a sigh of relief.”

Looking to the future Tony sees nothing but positives for golf for the disabled, “The way I’ve seen it grow since I’ve been playing on the European stage…I can see it only getting bigger and bigger. I can see there being some sort of world tour. I hope at some point that there’ll be more and more opportunities for us to play alongside the professionals.” As Tony approaches his 50thbirthday he has the distance to accept that some opportunities are for the young players, “I had the pleasure at St Omer, I played alongside Adem [Wahbi] and Brendan [Lawlor] in the group, and I was chuffed to bits because I was out with the good guys. I’d had a good tournament, to be honest, but at the end of the thing, oh God, I felt like such a dad, I was signing my card with them, and I just said to the guys, ‘Look, I’m going to sound so ridiculous now, but you guys are the future, and it’s good to see that the sport I love is in such good hands.’ Perhaps they are the future, and as more young golfers with a disability start coming through, it is they who will carry the torch.

So on reflection, what would Tony tell his five-year-old self? “Oh, I’d say stick with it, just try it, and learn. It’s such a good sport… it’s great socially, it’s also great for your health. It’s got so many benefits, but the euphoric feeling you get when you hit that good shot, I always remember the best shot of the round. That is the shot that keeps you coming back all the time. That’s what I would say to my five-year-old self, stick with it. I just hope I’m still playing in 10 years’ time to see these guys just take it to the next level.”

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions