Audio:

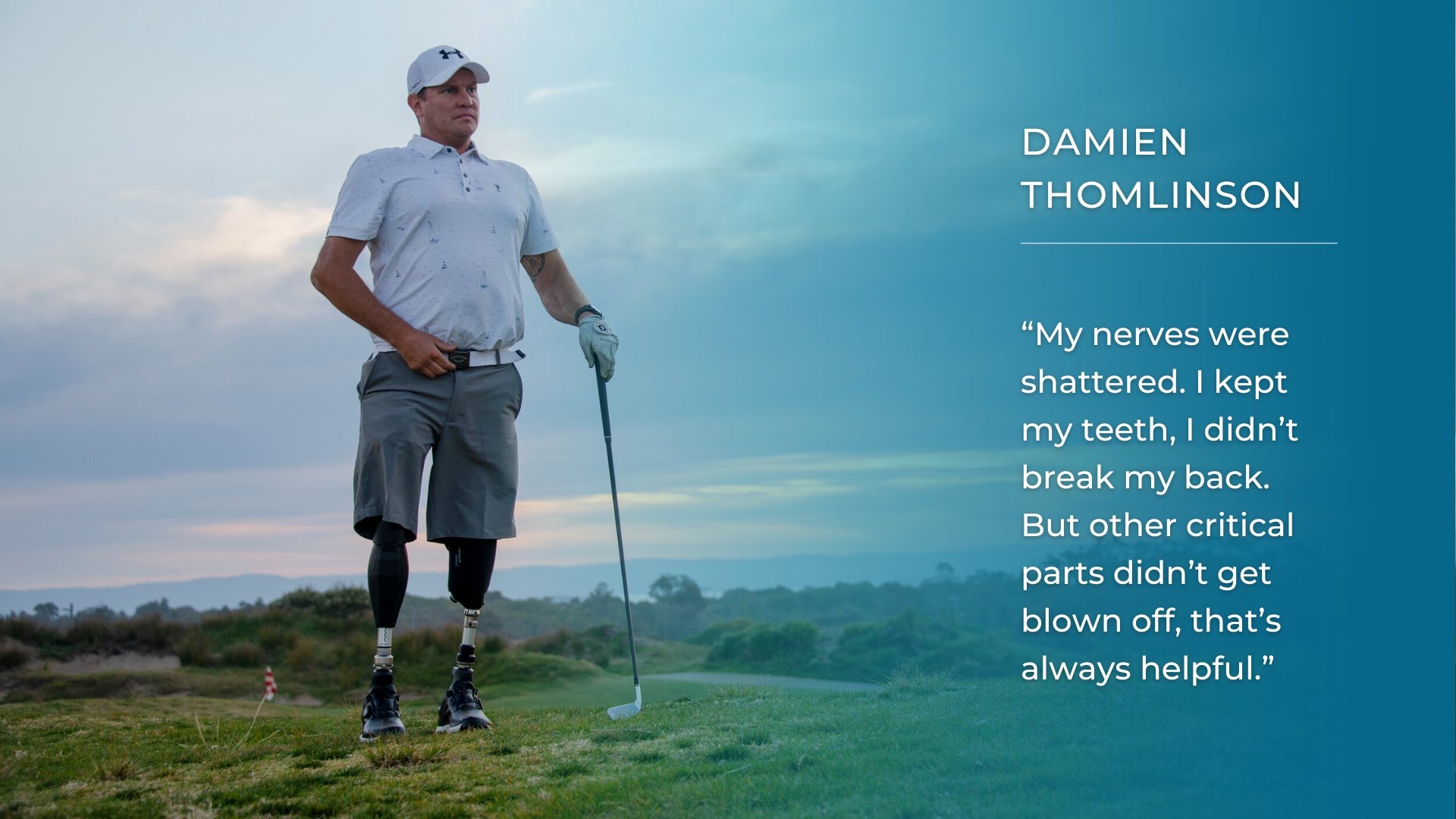

Standing in front of an audience, Damien Thomlinson cuts an impressive figure with a steely gaze. He is built out of battle, and his philosophy is worth listening to.

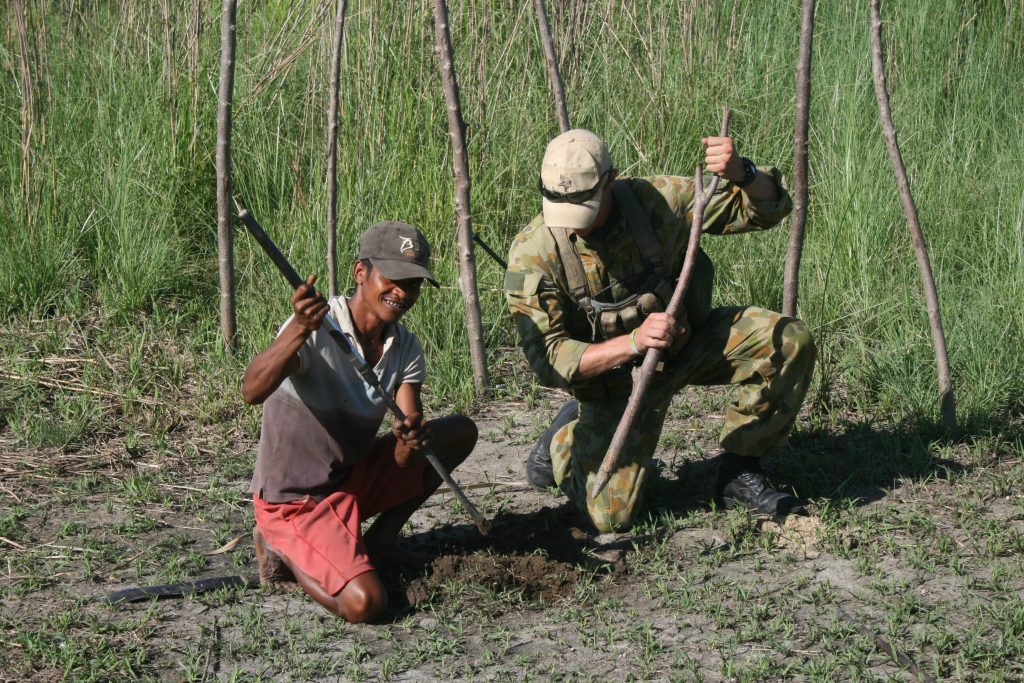

The former soldier served in Australia’s 2nd Commando Regiment – Special Forces – and he can tell his audience about how some of the most intense, pressurised military training in the world prepared him and his comrades to survive in deeply hostile enemy environments.

One of his favourite pieces of advice comes directly from that training: “Be comfortable in dropping the ball.”

At first, this sounds simply like a ‘be kind to yourself’ moment, until you think more about the actual wording. In the midst of great danger, in a place completely alien to you, at a critical moment, someone in your Commando unit will drop the ball. Hell will break loose. Your task is to learn to be comfortable in what happens next. As a motivational speaker, Damien shows others how to be a ‘Commando for Life’, to help us cope well with the ‘what’s next?’

Standing there on two prosthetic legs, it is advice Damien has had to follow himself long after leaving the Army. Sometimes he makes light of his leg and brain injuries, but he still needs the resolve to cope with the mental struggles of being a survivor. For there were friends around him who didn’t make it back.

The bomb went off on the road in Afghanistan in April 2009. The soldiers, and medics who arrived on the scene, had to work hard just to keep him alive, saying it was a miracle that he pulled through. He would lose both legs, brain and arms battered. He was close to death many times in the following days.

“My nerves were shattered. My face still felt a bit crap. I kept my teeth, I didn’t break my back. But other critical parts didn’t get blown off, that’s always helpful.

“I can remember just thinking, ‘I’m alive. My family are here.’ And you can see distress in people’s faces. So I was trying to just joke with them. There are pictures of me, blood on my teeth, still smiling, trying to tell everyone it’s going to be fine.”

In the decade that followed Damien used all the energy and determination from his Commando training to grasp back life, to walk again and look to the future. He has written a book, studied acting and earned a part in the movie ‘Hacksaw Ridge’, directed by Mel Gibson. He has represented national veterans’ charities, navigated rally cars in professional races, walked the famous Kokoda Memorial Trail with the father of a lost comrade, snowboarded for Australia in the World Cup, swam for his country in the Invictus Games and met and charmed the Royal Prince’s William and Harry.

Out of that whirlwind, two constant loves today are from quieter areas of life, his young family, and golf. Golf is the game that helps him keep his head level, combats the stress disorder still very much inside him, and makes him want to get out there in the sunshine every morning, listening to the birds sing. And after a great deal of hard work, Damien now plays off a 5.4 golf handicap.

He had been an athletic, energetic young lad growing up near Sydney in Australia but his father was worried he wasn’t heading anywhere. Then one day Damien saw an advertisement online for the Australian Defence Force Commandos; he was at his mother’s computer and on her desk was a picture of his grandfather, a decorated and twice-injured soldier from World War II. Damien signed up in 2005 aged 24 and was delighted to be accepted on the demanding training programme, surprising many people in his neighbourhood.

He says: “When I got qualified, I had a sense of accomplishment that was, I think, on a different scale to anything that I’d ever felt before. Not only had I achieved what I wanted to as a goal, I knew that you’re looking at 99 out of 100 guys that you speak to, the same guys who were laughing at you before you went; well, they couldn’t do it in their wildest dreams.”

Damien learned early on not to listen to the negative views of others but to trust himself.

“Most people’s opinions are just their anxiety coming to the surface, or their fear, thinking that they couldn’t do it.

“I had people laugh at me when I was going on Special Forces selection; they’d say, ‘Yeah, I bet you’re exactly what they’re looking for, mate, have fun with that’. So it was really satisfying to then drop a Commando’s beret on the table when you’re at a Christmas dinner, and say, ‘I guess I am what they were looking for after all’.”

This was a hugely positive and defining chapter in Damien’s life, where he made a circle of the closest of friends, trusting each other with their lives. However, the page turns and in April 2009, Damien was driving a modified Land Rover on night patrol in the south of Afghanistan when they drove over the IED bomb planted by the Taliban.

“I was driving it, it was a Special Reconnaissance Vehicle. The guy who was literally an arm’s length from me ended up with a couple of scratches and a blown-out eardrum. The bomb took my right leg clean off. My left leg was really badly damaged to halfway up the shin. My arms were shattered, my left facing a weird direction.”

Damien’s head was also badly injured.

He adds: “And that obviously rattles your brain. It’s like getting punched by Mike Tyson if he was the size of a dinosaur, but as fast as lightning.

“One of my unit had both hands on my chest, and I was trying to punch him to get him off. And he said it’s the most sickening thing he’s heard. He still wakes up to it now. Because in this arm, both bones were shattered. This elbow was hanging out. Everything was broken in it. The wrist and the hand were broken too.

“It still just amazes me that they could keep me alive. It’s hard to really rationalise it.”

Damien was transported to a hospital in Germany.

“I would wake up, sometimes just writhing in pain. So I had just enough of my brain to know what was happening.”

Doctors and therapists traditionally move very cautiously at times like this with a survivor, and families urge their loved ones to take their time. This thinking wasn’t in the Special Forces playbook.

“The entire system is essentially built around extremely difficult tasks, but especially when you’re in training, you’re given an unrealistic timeline. You’re given unachievable tasks to do.

“And it’s about training your mind to deal with the process of doing everything that you have to do, paying attention to every single one of those one-percenters, to ultimately know that you’re going to be somewhere five minutes late, which then means that the hostage is dead and you have to start the whole process over again.

“It’s a common thing for guys from my unit to recover quickly. I mean, I was walking within six weeks, and I was pretty messed up. I’m saying, ‘Look, let’s strap the prosthetics on. Let’s get this moving’.”

Damien wanted to be walking, not in a chair, ready for three months later when he would meet some of the returning comrades who had saved his life.

“I look back at pictures now, and I look really young. It’s a 28 year old kid, who’s just been ripped apart. You’re trained to be self-sufficient and operate in the most testing environments in the world, when your life’s on the line.”

Playing sport is often a successful part of the recovery process. While cricket and athletics were big things for Damien growing up, golf was always in the background.

“Golf for me, it was literally the conversation at the table where I grew up. My parents both were just mad golfers; that was their sport. Mum was a reasonably successful amateur. She played in Germany in a leading amateur tournament. My dad was always a reasonably good player. Before my injury, I was never really interested in the game. I could always hit the ball a long way. No one really taught me the ins and outs of what you’re trying to achieve, which is each individual shot going where you want it to, to then reach an overarching goal.

“When I came back to Australia, a lot of people were really, really good to me. I wanted to do something that could make up for what my parents went through a little bit. And they love golf. I thought, ‘Well, I’ll go out and that will be my thing. This’ll show them that I’m still me. I can still do the things that I could do before I had such drastic injuries.”

We were speaking to Damien after he had been on his home course that day at Magenta Shores Golf and Country Club, just north of Sydney, where he is enjoying being an ambassador for the club alongside European Tour professional Dimitrios Papadatos.

“I think the satisfaction for me, in preparing and doing stuff, was the same as it is now. Today I didn’t putt well. My stroke was reasonable, but I still did time on the putting green before I got into my car, before I came home, because it’s one of those things. You’re not going to fix the problem by sleeping.”

Snowboarding was Damien’s first great challenge after his injuries, scratching the itch of the thrills and spills of army life. “But I was literally racing against guys who are missing half a foot, which is pretty much a scratch. And you’re wondering why they’re so far ahead of you and there’s only so much you can do.”

Damien continues: “But about four years ago now, just before my daughter was born, I got new prosthetic feet. And both of those feet had a range of movement of about 26 degrees, as opposed to the 12 or 13 you get out of a normal [prosthetic] foot. And when I first tried them, I looked down and I thought, ‘It feels like I’m bending my knees. I could probably get a putting stroke out of this’. And that’s where it started. Then I went onto the golf course, seeing if I could keep the ball on the fairway. And each Friday night, me and my dad and one of his good mates would play together.”

Damien still suffers from a stress-related illness, though it’s difficult to explain it to others. Golf, however, continues to help him with this.

“I actually did a radio show with a lady who was in the London tube bombing. And she lost both legs as well. She was asking herself questions like, ‘What would have happened if I had not had my coffee that day?’ And she’s got all of these ‘whys’. For me, I have never had to ask myself why. I know why I was doing what I was doing. It’s not like you do a job in the most dangerous country on the face of the earth, doing the most dangerous thing you can, and you don’t realise that there is risk associated with it.

“Through the phase of recovery, there were battles that you go through, and the way that your mind works is odd. And some things triggered me in different situations that I’d had to deal with. The hard thing is it is getting worse. It’s weird. Right now, I know how to find the middle ground. I have to be active. I have to be healthy. There are a lot of different things I can do that can assist me in dealing with it.

“Last night, I had a moment where just one train of thought ended up taking over what was happening. And I had a physical reaction to it, which is the hardest thing. Because it wasn’t hot, but I was sweating. And it was a really… I knew what it was… God, the worst anxiety you could get.”

And at other times, Damien says: “One minute you feel like you’re just angry, you’re aggressive… And then two seconds later, you’re literally crying like a child.”

He adds: “I’ve found that for me to be able to deal with that, the game of golf has worked as a perfect leveller to give me something I’m working towards. And to take me off the loop of things that are happening in my mind. It’s given me something… I just find it works for me as like, I guess, a type of meditation, to go out and try and hit one of those shots. Just pick one and then go out and just drill it until my body can’t do anymore.”

He tries to explain further: “I’ve got a stress disorder that came with the recovery time of the injury more than the wartime and having to deal with some of the challenges. And golf was the perfect remedy for that. It works really well. As you know, the game can be really satisfying and then the next shot can be extremely humbling. The good thing about the game was it helped me emotionally to deal with some of those bad breaks. Because I want to shoot par every time I go out and I haven’t shot it yet.

“I hit the gym every day… I like training at times when I know other people aren’t. It’s a little bit strange like that. If it’s the nighttime and I can’t do anything, there’s a few guys I know who do stuff at night. Or I’ll be reading something. It’s like the endless quest to get just that little bit better every day.”

Damien adds: “I think the good thing now is being at the stage of my game where the mental side of things actually comes in. You’ve got to make the right choice at the right time and do a lot of different things that… I think it’s hard… It’s one of those that’s impossible to explain to people who don’t play golf, but everyone who does, knows the exact moment and those mistakes. They’re always really easy to see when you look back on what went wrong.”

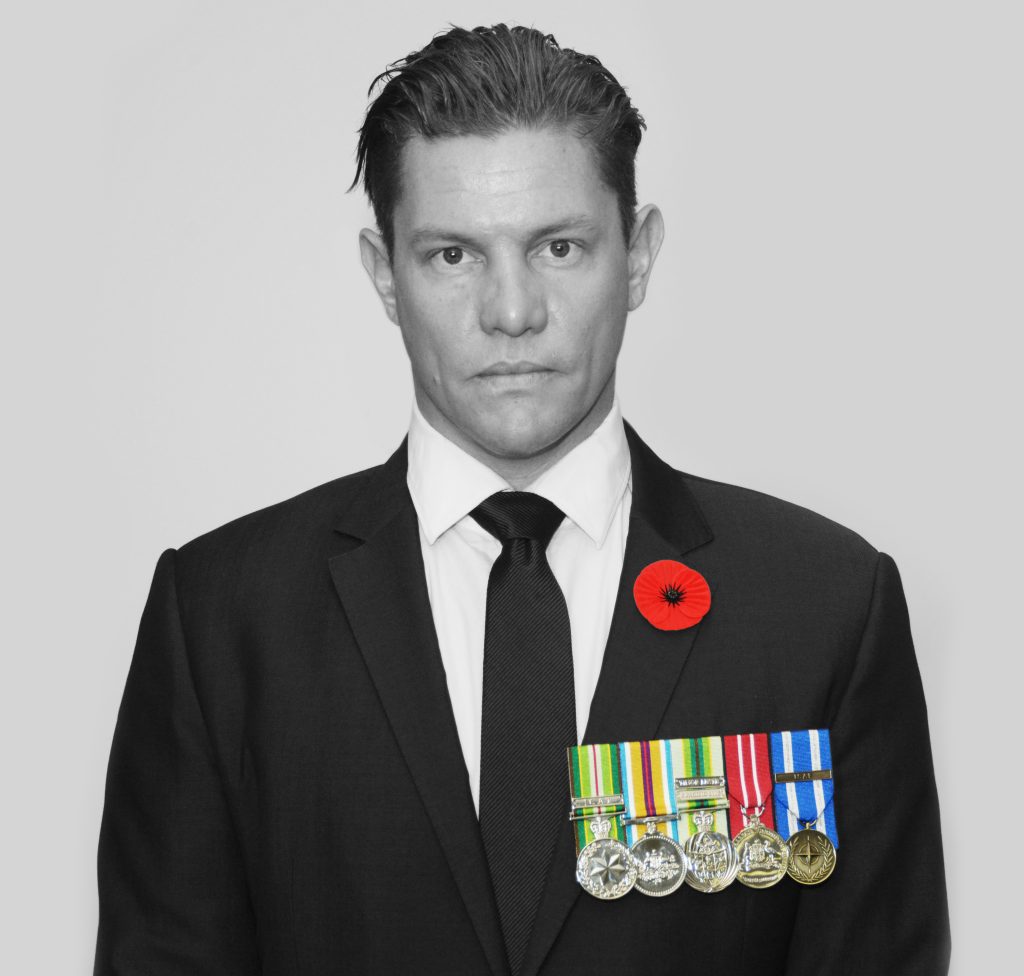

Recognising how golf mirrors life, the sport is part of Damien’s philosophy today as a public motivational speaker. It’s a role he takes seriously, looking to give others confidence while reminding them what it means to serve your country, the hard lessons of being a Commando. Damien has lost friends in war and also in the aftermath when life had become too difficult for them to continue.

“People have different levels of things they struggle with… And to me, I think Australians are pretty proud of what our servicemen and women do. So it’s really good to be able to take to them a story that reinforces how good a job our guys do.

“I think when my parents first heard about it, it was like a three or four per cent chance of me surviving. Doctors were baffled that I came through. They had a space blanket on me. If I couldn’t hold my body heat, I was going to die. It was that simple, and my parents were told this.

“The process of getting me into that position is a story that Australians need to hear, about the type of men and women that we have over there because, in the Special Forces, you operate in the dark.

“So it’s good to give people that little bit of perspective. I do get a big kick out people who say that just hearing the talk changed the way they look at adversity.”

For more than three years Damien studied acting professionally. His big break came in the much-acclaimed 2016 war movie ‘Hacksaw Ridge’, where Damien was cast alongside Andrew Garfield, Vince Vaughn and Sam Worthington. The film was nominated for Best Picture at the 2017 Academy Awards. Importantly for Damien, acting was also therapeutic.

“I found it fun that you could go in, and you could laugh, scream, cry, do whatever, while you were working on a piece. And you could essentially escape who you were. I think this phase of my life was me working out who I was, what really made me tick.”

The film led Damien to gain a spot on the very popular Australian reality TV show, ‘Survivor’. Geoff Nicholas’ wife watched it and it caught Geoff’s attention, who is a much-loved Australian professional golfer; seen as the Godfather of golf for the disabled by other players. The two men met and have become great friends, Geoff encouraging Damien into the competitive side of the game. Damien, who was playing off around a 14 handicap, would look at fellow golfers with disabilities like Mike Rolls (also a double amputee), Shane Luke, Stephen Prior and Geoff Nicholas himself, who are all low single figure players or better. This really inspired Damien to up his game and he thanks Geoff for being a key figure in his development.

“In Australia, it’s kind of frowned upon for you to voice your ambition. But if I’m competing against golfers with disability, I want to be the best one on the planet. I want to be ranked world number one. That’s just my goal.

“And now, in my mind, the way that I walk myself through things, it’s just a matter of time, effort and dedication to see whether I get there.

To reach these goals Damien has the best possible support from his loving family, including partner Abby, who is a teacher, and the young kids he dotes on, Ari Jay and Isla Rose. “They’re amazing. Isla’s like me, she’s an absolute pain in the arse. Every time I tell my dad a story about her, he’s literally just laughing, going, ‘She’s the exact same as you!’”

Damien’s 2013 memoir ‘Without Warning’ charts his progress of rehabilitation and he doesn’t hold back from criticising himself for being far too impatient with doctors and nurses at times early on. He still commits his time as an ambassador for charities DefenceCare, Soldier On, and the Commando Welfare Trust, which raise awareness and funds for injured soldiers and their families. Looking ahead, he will seek to play more EDGA tournaments, and striving to get to the top of the World Ranking for Golfers with Disability (WR4GD) will be Damien’s next great challenge, but also his daily therapy as he continues to look after his mental wellbeing.

“I like golf because it seems so simple, but it’s such a broad and complex game. Everything from the technique with shots, to the choice of shot, to the conditions that you’re playing them in. It’s just such a learning cycle where I think you’ve got to do something that, as an adult, you have to get comfortable with making the wrong decision. You have to literally be comfortable being the person who drops the ball.

“I love saying that during my talks. People talk about teamwork and what it takes to be in a team and all this sort of stuff. To me, the most important asset you can have as a team member is just to know the fact that at some stage, every single player on that team is going to drop the ball. It will happen. People are human.

“From there, how you deal with someone dropping the ball, ultimately assigns you a value as a team member. I really love the way that golf as a game reinforces that. You’re always ultimately the one that’s responsible, even for some of the bad breaks that you get. But I find that golf’s been one of those things that continually teaches me and reinforces the life lessons and things that I’ve dealt with in the past.”

Damien adds: “Ultimately, it gives me something to strive for. I mean, success lasts for 10 minutes. You know what I mean? That’s how long it lasts if you win a grand final or when you get your Commando beret. There’s those things that are really major that last for a day. I don’t know whether golf’s one that you can ever, ever, perfect. You’re always chasing the dragon. I really love that about the game. And I just like the fact that it’s me who is accountable for everything that happens.”

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions