“One day I woke up and thought I can’t live like this anymore… I just went to my local beach, and I walked into the water and thought, I’m just going to walk out there until I don’t have the strength to come back. I started swimming, and as I was out there I just had a vision of my daughters being bullied at school for what I was about to do, and I couldn’t go through with it. I did really want to finish it, but I thought I just can’t do that to my girls. So I came back walked into the kitchen absolutely soaking wet and…”

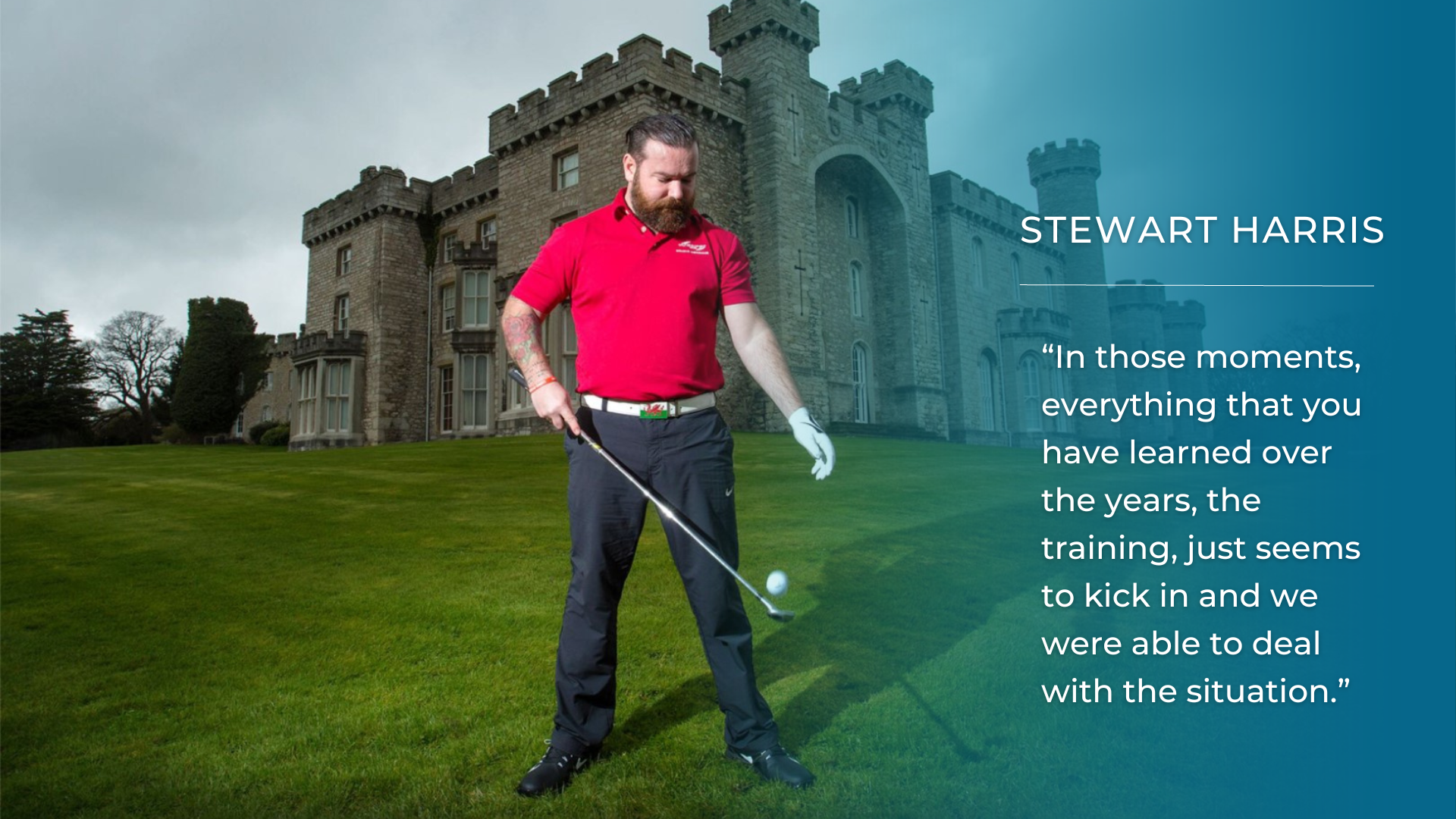

These are the words of former Welsh Guard Stewart Harris, who has experienced more in his 35 years of life than most will in the so-called three score years and ten. Married to Rhian with two daughters, Cerys and Megan. Stewart has lived a life of contribution, first as a soldier in the British Military, more recently as an ambassador for Wales Golf and generally as a spokesperson raising awareness of mental health issues.

Stewart’s story is filled with traumatic events, from which he has emerged with a life that has undoubtedly changed, but in some ways is better, he says. Although golf is now a significant part of his life, it was not always the case even though he grew-up with the nine holes links of Rhyl just around the corner. His father Kieth and brother Peter, both played golf and Stewart can remember as a youngster going to the club for presentation evenings and enjoying the atmosphere. But rugby was more his sport, not that he didn’t like golf, he just never got to play, and thought that perhaps he wouldn’t be good at it.

Stewart tried hard at school, was good at sport and never skipped classes, but he found that nothing used to sink in, but it was here in Rhyll that his life took the first of many twists and turns. “I didn’t do fantastically well at school, and somebody from the military came to speak with the pupils and told us that we would travel and that was something I really fancied,” says Stewart, who was told when he took the entrance test that he was too short to be in the army. Even so, Stewart went to Leconfield when he was on the cusp of being seventeen and took part in a two days selection process from which he emerged as the top student and so was no longer too short. “I picked the Welsh Guards because I loved London and the thought of living there was exciting, except we ended-up in Aldershot and didn’t go to London for a year,” says Stewart. Within a few months and still as a seventeen-year-old he was shipped out to Bosnia in Number Two Company for his first tour of duty. “I had to grow up pretty quick,” but the men with whom he served kept an eye out for the young soldier. “That was my first medal, and I had my eighteenth birthday there.”

Northern Ireland and Londonderry was the next tour which was due to last for two years as part of the peacekeeping force, but it was cut short when his company were informed that the British Army together with the Americans were going to invade Iraq. “I wasn’t sure how I was going to tell my mum,” says Stewart, but after a few months of training, he was off to Iraq in 2005. When he was told that he was going to Iraq, there was some worry, but he felt that as he hadn’t done any real soldiering now was the time. Stewart was reflective before saying, “I was a very young man and so was hungry for some sort of combat it’s almost like a footballer training and not playing, or a golfer training but with no competition. I had years and years of training and hadn’t had an actual firefight yet, and so when Iraq happened I thought I am actually going to do something real now. I was hungry for it, and I see that same hunger now when I speak with young soldiers, but if I were to tell them now, I would say be careful and be careful what you wish for. I came back unscathed and remember coming home from that tour and thinking, nothing is going to be as bad as that.” The snatch landrover in front of his had been hit by an Improvised Explosive Device (IED), and it was then that he first had to administer morpheme to an injured colleague. He hoped it would be available for him should he need it.

After that tour, Stewart started to put down some roots for his family. He became a recruiter for the Welsh Guards for a couple of years during which time he bought a house, had a second child and got married, and with most nights at home, it was a good time for his family. Stewart’s next mission saw him swap weapons for cameras as part of a reconnaissance group in Kosovo, where human trafficking, drug trafficking and money laundering were rife, his job was to observe and feedback to special forces. Then came Afghanistan in 2012.

“I thought it couldn’t get worse than it was in Iraq, but I couldn’t have been more wrong,” says Stewart. Daily contact was the norm. It was during this tour that they lost their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Thornloe. Stewart recalls his commander, “He was a terrific leader, who led from the front. He died because he was letting a guardsman have a rest, had he been inside the vehicle then he would have survived the IED which took his life.” Stewart was in the bearing party consisting of eight members of the Welsh Guards who then shouldered the coffin of Thornloe and carried it into the chapel. On that tour, he lost five more of his colleagues.

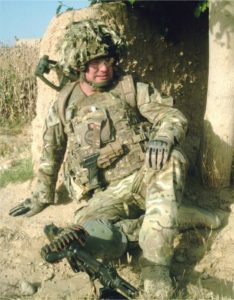

Later Stewart was deployed as part of a ‘Police Mentor Advisory Group’, where their job was to teach and help local police look after themselves. Four months into the tour and things were going quite well. Sangin in North Helmand Province is known as ‘bandit country’. He decided not to tell Rhian exactly where he was going, as it was an infamous region. On the 1st of July 2012 Stewart would find out just how dangerous it really was.

The eight-man team that walked into a Taliban ambush was unaware of life-changing experience that was about to unfold for the five survivors. On that day, three of his colleagues would be shot dead and his commander was shot in the leg, there was no air support due to the rounds that were being put down by the Taliban. “It was a hot zone. A killing area. I remember thinking that this was it. As they were coming closer, I remember being engaged from the front, I remember being engaged from the right, from the left and the back, they were just coming from everywhere, and the rounds were pinging off the vehicles… I thought this is where we were going to die,” recalls Stewart “In those moments, everything that you have learned over the years, the training, just seems to kick in and we were able to deal with the situation,” Finally air support was able to get into the area, pick-up the wounded commander and put fire into the compound. The immediate danger was over, and the team got back to base.

There is little or no time to grieve in war. In a couple of days the soldiers are back doing their job, with a different team but instantly they have to get back into the old routine of work and life. “You never forget but it is back to normal, and perhaps, as there is no time to grieve, that is why so many young men come back home and have difficulties. You get visited by all these generals and they, say well done, good job, you did fantastic, there is nothing else you could have done, and to a point they are right, the only thing that you could do to stop it is not to be there.”

It is when active military personnel get back home and have some time when they feel it most, Stewart explains, “I will never be loved as much as I was by members of that team there is some sort of bond that is forged in combat, to die for someone else, to give your life for another you become a band of brothers and you will never find that anywhere else. As soon as I got home I just wanted to get back out to Afghanistan, I felt guilty knowing what they were going through, I felt guilty for being at home, for sleeping in my bed, I felt guilty for being with my wife.”

Stewart had his two weeks of rest and recovery at home but was anxious to get back and see the guys. “I was back to work, and we were out on patrol on Route 611 when we got hit by a massive explosion under the vehicle.” The IED had thrown the vehicle through the air, “Everything went dark, it was a blur after that…I remember thinking that I was in hell, I thought that the devil must have been Scottish, but in fact, that lovely voice was from a very dear friend of today, Dr Kirkwood who works at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham. He explained that I was back in England and that Rhian was in the room, but all I could think was, why is my wife in Afghanistan?” After the blast, Stewart had been air-lifted back to Camp Bastion, was sedated and flown back to the UK. It had been just four days since the accident, but most of it Stewart can only piece together through what others have told him. The IED had damaged three of the lobes in Stewart’s brain causing blindness in the right eye and partial blindness in the left, due to the blast he was deaf in the right ear and partially deaf in the left, and physically the explosion had crushed his right testicle while the other was now located in his stomach.

The ‘Defence Military Rehabilitation Centre’ at Headley Court was full of people who were injured in Sangin. The facilities at Headley Court are second to none which helps to keep morale up. “I had all my limbs, but I would walk around there were guys with just a body and arm and a head. There were double and triple amputees, and so I think that it was a case [of thinking] there that there is always someone worse off than you.” With the magic of modern medicine, Stewart has regained much of the vision in his left eye, hearing aids have helped him to regain some hearing, and so the physical side of his recovery was quite quick, but he was struggling with day to day tasks and feeling down. “I became not a nice person to be around, I became snappy with my wife and children, I didn’t think I was good enough for them anymore, I asked my wife to leave me and take the children,” says Stewart, who was diagnosed with ‘combat post-traumatic stress disorder’. The recurring nightmares, flash backs, and random thoughts that are associated with PTSD are as Stewart explains in part due to miss filing in the brain, “Everything in your life is filed away in your brain in the right place for when your brain needs to access it, and so what happens is when you see or experience something traumatic the files get put in the wrong place or not even filed at all. So when you are having a cup of tea, this file will come from no where and you will start to feel and start crying your eyes out. I remember tying my shoelace, and out of nowhere I just burst out crying to the point where I couldn’t breathe.”

Stewart had changed and was having difficulty coming to terms with his new behaviour, “I did try and get some help…but the military and the soldiers have a job to do, so when you are not in that role you have a back step and mental health was sort of taboo, it was a case of man-up and sort yourself out, so I would keep it to myself.” When Stewart walked into the kitchen of his home, soaking wet after his dance with death, Rhian at first did not realise what had just happened, “My wife was, like where the hell have you been, and I just told her what I was about to do, which was really difficult I had to tell my wife that I was about to leave her without even saying goodbye. She was fantastic throughout everything, she called 999, and I was placed in a mental health unit.”

Flippantly Stewart says that “a mental health unit is like the worst all Inclusive hotel, once you are in you can’t get out,” but it was just what he needed at the time and in his words, “Take it one day at a time, baby steps and things will get better.” Martin, a veteran came into the unit one day and said “does anyone want to come golfing?”, Stewart’s response was simply “Does it get me out of here?”

It was at this stage that golf came tearing into Stewart’s life. At the driving range that day, he spread forty-nine of the fifty balls in his basket all over the field, but any golfer will tell you that it just needs one shot. One shot that comes right out of the middle of the club, one feeling in the swing that is as smooth as silk and it was that one shot that grabbed him by the shirt and pulled him into the game. “Golf is my medication, it is what I go to when I am not feeling good, it has opened so many doors for me. I am a healthier person for it, not just physically, but it is also social.” Stewart recognises that when he plays with three new people, by the end of the round, they are already friends and that golf can be played by people of all abilities and with all disabilities. Stewart remembers, “When I was still in Headley Court, one of the lads came in buzzing talking about playing golf, and I was thinking how can you play golf, you haven’t got any legs.”

Stewart offers his advice to others who are facing physical or mental health challenges, “Please don’t panic it will be ok, things will get better. It’s going to be alright. Take it one day at a time, your life will change, but who knows it could be for the better. You can still go on to help others do amazing things.” Some of those changes have helped Stewart become a role model for others. He has played golf in national championships as a golfer, not as a disabled golfer, has climbed Mount Kilimanjaro and the Three Peaks, and has been instrumental in introducing a new scheme within his community: bringing in free swimming sessions for veterans at the local pools in Denbighshire.

Overall life is good for Stewart who takes one day at a time and helps other to realise that change for the better can happen and that new memories can be created. One such day was in 2017 when together with his dad they played golf at the Open venue Royal Lytham and St Annes, and in doing so created a memory that will never leave either of them.

Contact Stewart

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions

Banner photograph by Rachel Argyle.