The 1980s, and that moment when you put the vinyl record on the turntable and lower the needle down, watching and hearing the revolutions before your favourite song, you’re approaching the future with excitement.

But occasionally the needle or the record player lets you down. You don’t get to hear that song for a while.

Declan Burns, 55, grew up in Derry in Northern Ireland in a close family which loved the game of golf, and young Declan was forever at a local club while his parents played or attended a social event there; he would be happily drinking a juice or pop, and chipping and putting and making his first golfing friends.

Then, as a university student in Manchester, like many young golfers, he drifted away from the game; in his twenties he was immersed in London life, in the music studios as a sound engineer, working to capture the best sound for the rock bands.

Not long before his 30th birthday he suffered a horrific motorbike accident on the M40 out of West London. His right arm was paralysed but he would sustain many other injuries including to his spine, neck and hips, on this homeward-bound night-time journey in May, 1998.

Declan survived but rehabilitation in those days wasn’t as sophisticated and he later found himself in pain, limping along the streets of London with his paralysed arm in a sling like, as he puts it with his feeling from the time, “an absolute human disaster”.

“People kind of clearing a path, not looking you in the eye, and it’s like, oh man, how long can this go on? Hindsight is great; you can even look back and see the funny side of things, but at the time I did find it very frightening and very difficult to look after myself. Life was hard.”

Declan would eventually have the paralysed right arm amputated 12 years later in a positive move for him, but around the time of the accident a major infection occurred in his left arm (which had also required surgery); nearly losing this arm as he fought the super-infection ‘MRSA’ in hospital isolation for three months, relying on the help of PPE-clad nurses to feed and look after him, and help him stay alive.

So far, so bad… He would lose his place in the music industry but his resilience then kicked in, fighting for small gains through slow recovery, before a little later studying for a Masters degree and starting a second career: all testament to Declan’s remarkably tough inner core, while he saw things in black or white: to pick himself up, or give up. That was the choice.

Looking back as a Derry resident once again, his comeback is indeed striking. Helped by his family, Declan has excelled over two-and-a-half decades to find professional success, while being married for 22 years to Koran, a recently retired district manager in the Library Service, with their kids Terry and Amy.

Meanwhile, that thread from the past in his brain titled ‘Golf’ today gives Declan a wonderful outlet in terms of building physical and mental strength, finding new social connections and helping to add the confidence that he recognises is all part of the psyche needed by anyone when the best laid plans fall apart because life gets in the way.

About his golf, and recently his playing in EDGA G4D (golf for the disabled) events, Declan says: “I have genuinely loved it, from the variety of people you meet and the variety of abilities that you encounter; seeing how those people with impairments play golf, is just mind-blowing. For anyone who has a disability who doesn’t play golf and may be interested in it, just to witness these people play golf and surmount the difficulties that they face to play the game, is inspiring for me, it really is.”

Declan’s father Tommy Burns was keen on the Irish sport of hurling and Declan followed suit; this attachment to bat and ball transferred readily to golf which he soon loved playing. The family would sit together at home and watch on television ‘Around with Alliss’ and then later the likes of Palmer, Nicklaus, Seve and Faldo battling it out on the Old Course and other iconic venues at The Open, all in front of them in their living room.

That thread never quite broke even though Declan stopped playing when he became a student at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), completing a degree in chemical engineering.

After ‘uni’ he moved to London to study the guitar. He rated himself as a decent guitarist then and loved all the “rock shredders” like Stevie Vai and Joe Satriani and the metal bands like Dokken, AC/DC, Van Halen, and Living Colour. He followed the underground sub culture bands from American record labels like Sub Pop, whose acts included Mudhoney, L7, Nirvana, or new-wave punk bands like Fugazi and Black Flag. Then there were the British/Irish bands like Gaye Bykers on Acid and That Petrol Emotion (whose main members were formerly of The Undertones, also hailing from Derry).

Declan got a job in a busy music studio, at first loving being a sound engineer but the brutally long hours attending to the needs of record labels killed his enthusiasm as he found himself sleeping under mixing desks too many times. Instead, making master recordings and remastering became his speciality including working on the entire Iron Maiden back catalogue with producer Simon Heyworth, who worked on Tubular Bells with Mike Oldfield, and Declan also supporting artists such as Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull and members of The Alarm and The Cult.

Everything changed in an instant. When returning home to Bethnal Green, Declan’s Kawasaki Zephyr 550 crashed into a barrier on the M40. He spent his 30th birthday in the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (Stanmore) in North West London.

“I think it hurt my mother so much because she was so far away at the time. She made the trip over to come and visit me in hospital. That was pretty traumatic. You can cope with everything by yourself until you’re confronted with that level of emotion, and then it just consumes you. It was all a difficult time, but I also had a lot of support in the ward around me.”

Indeed the kindness of strangers marked Declan at the time, he looks emotional as he recalls the generous help of one particular gentleman patient.

“We used to gather there [just outside the hospital near the ward doors] and have a cigarette and get back in before the nurses could see you. But there was a guy at the very end of the ward who had been an army engineer, and he saw me shuffling my way across the floor trying to get outside, and kind of tapped me on the shoulder one day and said, ‘I made this thing for you’. It was an old coat hanger, and he basically twisted it and shaped it, and made a little harness that sat over my head, with a little kind of holder for the cigarette, so I could reach over, pull it up, take a smoke of a cigarette, and then put it back down again, and be able to stand there without it staining the side of my face or the smoke getting into my eyes.”

Declan adds: “But it’s a different life in hospital to when you’re then thrust back out into the community with all of these injuries and all of these medications to take and your own life to look after. It was very daunting because I was very fragile. I lost a lot of weight. I lost all my balance. I was injured, a lot of impact in my hip, so I was in a wheelchair for a while. Trying to survive in London when you’re a healthy person is traumatic enough, but not when you’re carrying those levels of injuries. I found it really frightening to be in London at that stage, particularly on the underground when you’re trying to make a journey.”

The accident had caused Declan to suffer an ectopic bone formation in his left elbow (his better arm). They had to wait for the bone to form for 18 months before they could operate, so it had to be fixed in a set position away from his body. Declan had a lot of difficulty eating, shaving and washing as he couldn’t physically touch his face. Waiting for the necessary operation on the National Health Service could take another two years so Declan went into debt to get the surgery privately; the success of which operated his hand again and released his elbow properly. The first time he was able to touch his face for nearly two years left him in floods of tears.

The needle would break on the vinyl another time. A little after the surgery, the left arm became infected: the dreaded MRSA led to three months of isolation as he was “pumped full” of anti-bacterial drugs before the infection was finally quashed for good.

Finally set free, Declan later proclaims his much battered left arm to be more or less fine accept for the inability to rotate his forearm from the elbow, which means him needing to use a lot of shoulder and upper body in his movements. All actions in this area, like picking up a dropped pen from the floor for example, need a plan.

The biggest plan soon became easy; back to Derry and Declan and Mum Bridie could help each other through it. “Mum had been distraught at being so far away. People face challenges in their lives, and it’s all about how you get up and get beyond them, and you have to endure it at the time. So it’s that attitude that you take. I found that having a positive attitude to wanting to get up and beyond the injuries is what helped me recover, staying reasonably mentally strong at the time. It’s a fight that I think a lot of people take in many different forms. Mine was just obviously physically traumatic.”

Imagine then a young man being forced to give up the guitar after all his work in that area of music.

“Either you react to it or you suffer from it, I don’t know. It’s that black and white for me, and I’m very much a fighter, so I’ll try and make the best of a bad situation,” says Declan.

With good support, including from his elder sister Carmel and a group of music-loving friends who welcomed him back to his home city, Declan’s confidence gradually returned. He would enrol at the Ulster University Magee campus in Derry, developing his computer programming skills, taking a Masters Degree. Today, he has a successful career as a manager working for one of the largest software companies in the world.

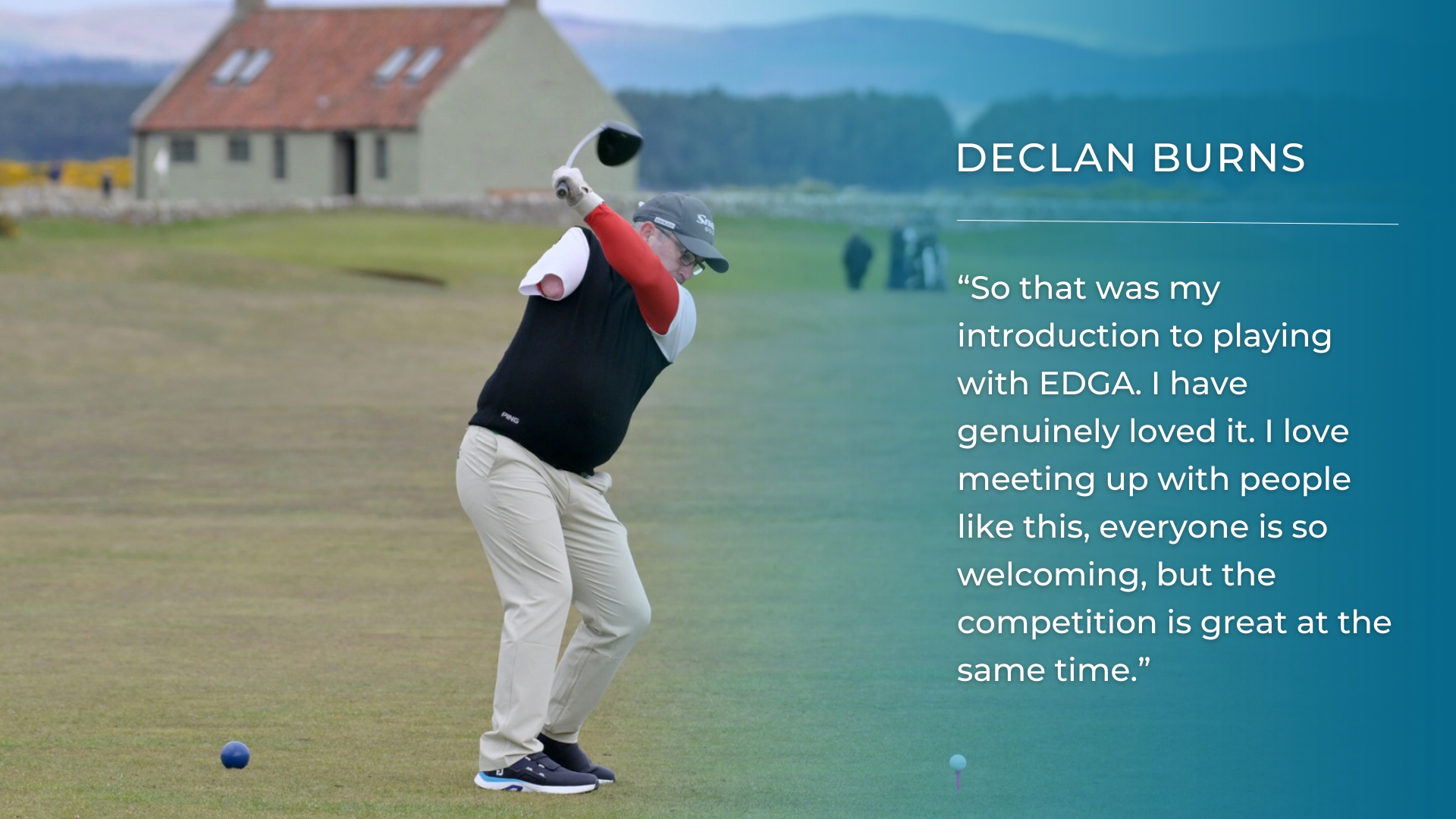

For a time, he worked for an American insurance company, and he was drawn into starting a golf society to assist with employee morale. So Declan had suddenly found golf again in around 2005, going to the range and taking some lessons at the Foyle Golf Club where he still plays to this day, and he thanks the excellent PGA coaches Sean Young and Derek Morrison, with the latter helping him to understand what he needed to create a stable swing. This he did while cursing every type of miss-hit, from the topped shots, fat shots, slices and shanks. But the hard work has paid off and Declan has become a regular, competitive and fulfilled golfer. He plays in the stance of a right-handed golfer and uses his left hand in a backhand swing. He says golf is good for his fitness, core strength and building confidence in how his body operates today.

Declan played in his first ‘G4D’ events by finding the Society of One-Armed Golfers, which was established in 1932, and then last year in 2022 he played in his first EDGA event, the Irish Open.

“So that was my introduction to playing with EDGA. And you know what? I have genuinely loved it. I love meeting up with people like this, everyone is so welcoming, but the competition is great at the same time.”

The highlight so far has been when Declan travelled over to Scotland, to the Home of Golf, to play in the EDGA St Andrews Links Open on the Eden Course, which included taking in the Old Course before having a few beers at the famed Jigger Inn near the Road Hole.

“The Road Hole, the 18th, and soaking in all of the scenery around it and standing on the Swilken Bridge, and the hairs on the back of my neck were upright. It just felt so special to be there. It’s almost like hallowed turf. I’ve seen this course so many times on TV, and my whole life revolved around golf. When I was growing up, my parents played it, my aunts and uncles played it.

“We always went to the golf course for dinners. My parents, I would sit and watch them get all dolled up with suits and fancy skirts and dresses. And then also sitting around the TV watching ‘Around with Alliss’, and he’s walking up the Road Hole and talking, and it brought it all back to me. I thought, this is just amazing being here. The whole weekend, I was so inspired to be there.”

Declan adds: “I’ve got to a stage now where I feel like I can actually play the game again. I can stand behind the ball and think there’s every chance I’m going to hit this reasonably well. Of course, not every time, but being able to get out there and play 18 holes competitively. I play with able-bodied golfers; I beat them or I challenge them. To be seen as someone who plays equally as well as anyone else on the course, that’s a big achievement for me.”

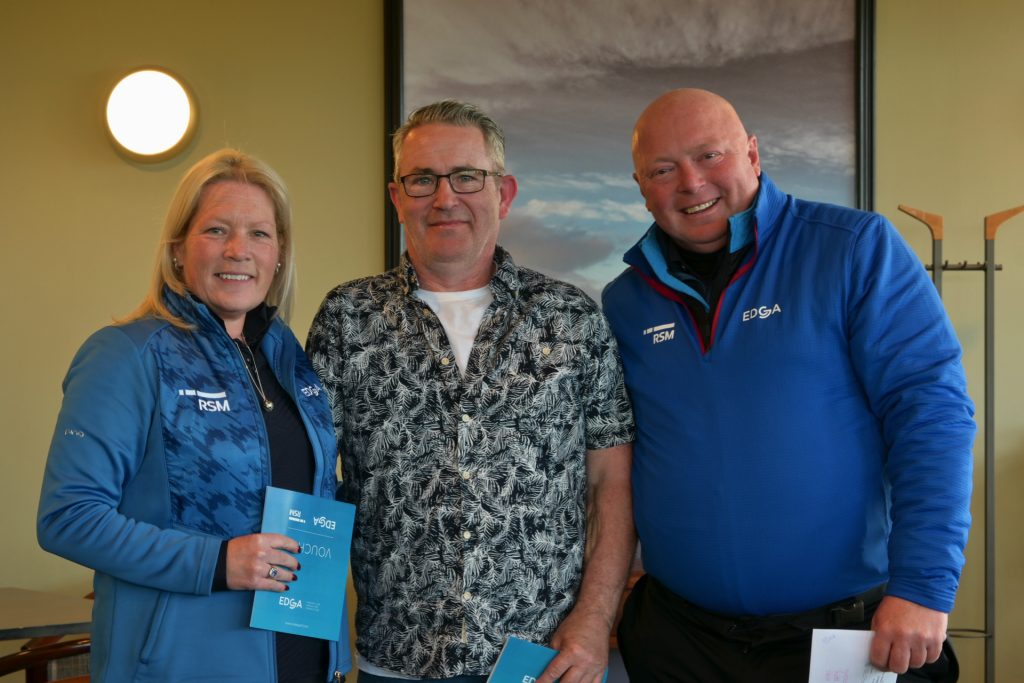

Declan enjoys the competitive set-up in EDGA, the EDGA Tour events offer Gross, Net and Stableford divisions. Within this framework, he can show his competitive edge with his golf handicap of 21.4. And recent strong EDGA performances have led to him climbing the World Ranking for Golfers with Disability, qualifying for the RSM European Net & Stableford Play-offs at North Hants Golf Club in England in mid September.

“Everyone is playing off the same level playing field regardless of the disability and you’re on a ranked scale. Now, I didn’t get into it for that. I think it’s a positive side effect and I have enjoyed climbing the ranks, and I genuinely didn’t expect to, but the fact that I got invited to the RSM European playoffs is a huge bonus for me. I think it’s consuming me right now, and I just cannot wait to get there.”

Remembering the family watching golf together on television, he says he is proud of how his Mum and Dad worked so hard from difficult beginnings, Dad Tommy eventually working in community relations and Mum Bridie enjoying a nursing career that led to caring for many people with severe physical or mental disabilities.

Declan concludes: “It started as a happy family day out as a kid and while there are days when I’m on a course playing badly and inwardly cursing myself, I do remember those earlier times with a lot of fondness for how the game brought us together, sitting around the TV watching the greats in action.

“I love to play golf because I love those rare occasions when everything comes together and you play well, hitting the sweet spots, making those chip shots look miraculous and the putts dropping when they should. It’s a bit like music in that it is rare that everything just falls into place, but this only adds to the magic and mystery of it all.”

Contact EDGA

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions