Former US PGA Tour player Ken Green will tell you that the “extreme highs and lows” of golf are both required, together, to feed the soul. You can’t have one without the other. It’s the good and the bad.

When he first eyes you up it doesn’t immediately appear that he is going to use the words “joy” and “love” a lot. But he does. This man’s quest to continually find joy in the sport – despite the challenges he has faced – is a learning that many other seasoned golfers could follow, if they are listening.

Listen to Ken talk about golf for a while, and a more important door opens.

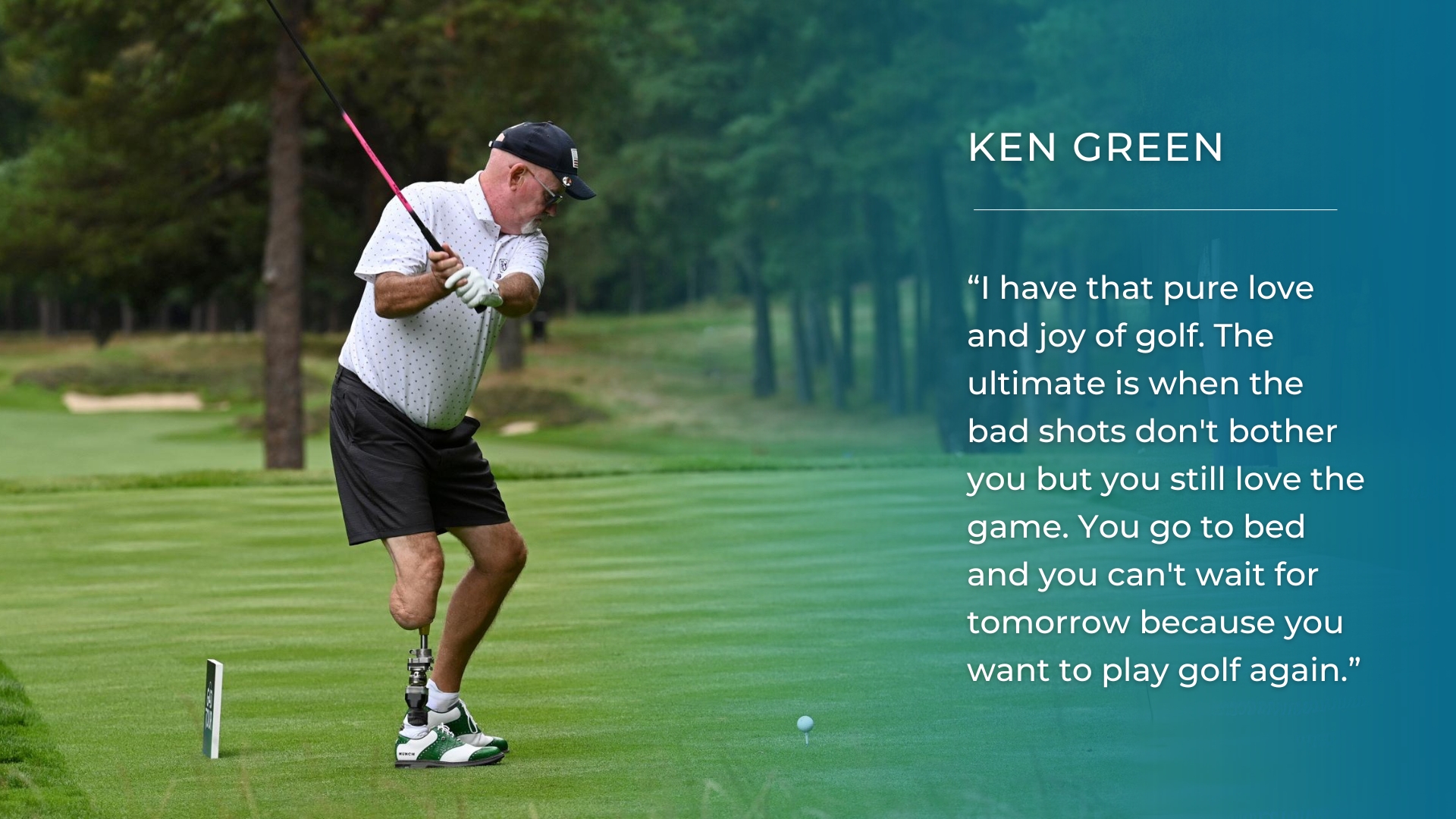

Ken plays as a right lower-leg amputee, but he often does so while enduring intense pain due to a chronic nerve injury condition. A 65-year-old who still competes, in part, to shine a light for others on the unique benefits of the game he loves, the game that makes him want to get up in the morning and play again.

This unusual game in which, though we might not be able to hit it nearly as well as Ken Green – a player who used to compete regularly against the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Tom Watson and Seve Ballesteros – but after speaking with Ken, we certainly want to try.

“I’m not playing golf as a professional anymore,” explains Green, originally from Connecticut but who now lives in West Palm Beach, Florida. “I play it for different reasons: my own love of the game and my hope to help others. So I have that pure love and joy of golf. The ultimate is when the bad shots don’t bother you but you still love the game. You go to bed and you can’t wait for tomorrow because you want to play golf again.”

On a now rare visit to the UK last September, the news of Ken Green playing in a ‘G4D’ event (golf for the disabled) in England was always going to be more than a headline.

The G4D Tour BMW PGA Championship at Wentworth was one of nine major international events in the 2023 schedule (staged by the DP World Tour and supported by EDGA) which attracts the leading players with disability in the World Ranking. When Ken was asked if he could make the trip, he was immediately enthused.

Though lacking a little in regular practice, he was still very much competitive as the elder statesman among the players, knocking it around the West Course, one of the most challenging on the DP World Tour international schedule, in 77 and 80, finishing in a tie for seventh.

He said afterwards that he really enjoyed the experience, happily taking part in interviews with the media, including the team from the DP World Tour; imparting his desire to encourage others to join in with this game and love it like he does. In return, Ken learned about EDGA’s ‘player pathway’. EDGA, supporting the G4D Tour as the acknowledged experts in all things G4D, ensures that people with a disability have more opportunity to sample, participate and compete in golf.

“I believe that’s my job now. I had my day in golf. Now it’s not about Ken Green anymore. It’s about life, which is far more important and you learn far more through the big picture. When I look back since the accident and all the things that have happened, and how I’ve grown, a lot of it’s through the game of golf. I went from being one of the best golfers to being a brand new golfer. I learned that it’s okay to try to get better as a golfer, but it’s far more important for me to try and help other people who might be a little stuck.

“And every person you help multiplies because if it’s a young boy of 13, he goes on to have family and they have a family. So you’re not just helping one at a time, you’re helping hundreds and hundreds. You may be helping a person who some day cures cancer, you just never know, so that’s why you should be happy every time you help one person.”

In the 1980s professional golf was full of great names, superb players. Ken, who played 508 US PGA tournaments, did things his own way. Establishment figures were wary of his temperament that could sometimes appear spiky, which Ken would say was self-expression and being honest, while his talent, hard work and record speaks for itself.

The name ‘Green’ (he also nearly always wore an item of green clothing as his trademark) was also seen on a great many leaderboards in the mid to late eighties, Ken winning amongst others the Buick Open (1985) and the Canadian Open (1988), and a total of five US PGA Tour titles. 1988 was a landmark year and Green’s effort to win the Westchester Classic in front of home crowds near to where he was raised resulted in him being part of a famed four-way play-off with Greg Norman, David Frost and Seve Ballesteros. The Spaniard’s short-game grabbed the title but during the fight Green showed how much he cared about the game and its fans.

The veteran’s presence at Wentworth thus commanded respect from the younger G4D Tour players for varied reasons: the dynamic rhythm he still finds in his swing circa 2024 remains impressive to any onlooker; his amazingly positive attitude in playing while clearly in pain with his condition, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS); and thirdly, well, the reference books have Ken on a par with the likes of the aforementioned Watson and ‘Seve’, and Payne Stewart, Curtis Strange, Tom Kite, Nick Faldo and Bernhard Langer in tournaments during the 1980s, and then playing with, or against, all these great names in the legendary 1989 Ryder Cup match at The Belfry, England (Green earned two points out of four for America, where Europe retained the cup in a thrilling 14-14 tie).

It was two decades later, in 2009, that Ken’s life changed in tragic circumstances. Green was a passenger in an ‘RV’ motor-home accident. While travelling home to North Carolina from Texas, the vehicle had a tyre blow-out and hurtled down an embankment; Ken was the only survivor of the crash that resulted in the loss of his wife, his brother and his dog.

Golf had already helped Ken to get through a very troubled childhood in Honduras in which he suffered sexual abuse. Golf would be an escape then, and it became his identity: “professional golfer”. He is quoted as saying: “If I hadn’t fallen in love with golf, I don’t think I would be even standing here, to be honest with you.”

Ken, who found faith in God, added: “I think I would have done what happens to a lot of kids that get abused like this and drink alcohol, take drugs and all that. So golf had already saved me, and it was about to save me again because obviously I knew that I couldn’t ever play professional golf. I was okay with that.”

A year after the accident, Ken’s son Hunter died of an overdose.

Ken Green’s later autobiography, entitled Hunter of Hope: A Life Lived Inside, Outside and On the Ropes, would record these sad events. On the front of this book, there is a quote from former Ryder Cup US team captain Paul Azinger that reads, “One of the most courageous men in the world”.

Regarding his own outlook, the accident had left Ken facing significant injury challenges, including that he had little option but to have surgery to have his lower right leg amputated. At that time he will tell you that his leg injury didn’t really matter in the scheme of things. But as time moved on, golf – the game, its processes and its people – did start to matter to him again.

“For me it was like, all right, I can either sit and cry and moan, why me? Or I can say, Wow, I get to play golf all over again. I get to learn it again, find out what I can and can’t do. I know that sounds weird, but you have a brand new world that’s coming your way. Sure, some of it sucks, but you can overcome that and that’s a ‘W’ [a ‘win’], and you won’t have many opportunities to have a second life.”

Ken may have embraced the challenge but he found that finding his swing again was no easy task.

“It was definitely a learning curve. I still played pretty good golf even though I had turned 50 [before the accident]. And all of a sudden you’re hitting shots that are like, oh boy! You’re topping shots and you’re learning lies, angles, hills, and literally hitting shots that you would never have hit in your entire life! You sit there and just laugh at it, but that makes you think, ‘I’ll figure it out, I’ll get it’, and eventually it’s pretty good.

“I had to understand there are certain shots I’d never be able to hit again. The leg will not allow me. I need that foot to hit that shot and I know it, but I think I’m going to pull it off anyway. And so that took a while to get through and I’m still fighting it. But chipping was brand new, bunker play was new. You don’t even realise you used your leg that much, it was far more important than I ever dreamed. But you just keep at it. You go out there and you keep grinding and you’ll get better. It doesn’t matter how good you are or how bad you are, if you work at it, you will get better.”

More recently Green was diagnosed with a so far incurable condition called Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), believed to be caused by his amputation, in which in simple terms the pain from a physical trauma outlasts the expected recovery time. Ken’s drive to raise awareness for this condition added to his motivation to play on the G4D Tour at Wentworth and in other G4D events, like the recent USDGA event supported by the PGA of America in April (2024).

“It’s a brutal disease. I mean the pain you go through at times is mind-boggling. You’re curled up into a little baby foetus position and you’re waiting it out. There’s nothing strong enough to stop this pain. And you have to just wait it out and then you feel okay. It’s called the suicide disease. I understand because I’ve been really close. I don’t care who you are, everyone’s got a line.”

Thankfully, Ken says he is no longer near that line, being careful to ensure he manages the pain properly, which can be set off by different triggers. It’s a learning game still. Life is a huge challenge, he knows, but now playing golf is offering an altogether friendlier challenge, one far removed from the pressure of earning a living by your score and chasing trophies.

Ken says now: “Golf stays in your head. It’s more than a game. And that’s part of the challenge of the game and the fun of the game. That’s why golf is so good for people who have been thrown a curve-ball in life, it makes for a brand new world. Age doesn’t matter, you’ve got a brand new world to go and attack. That’s great.

“[As a G4D player] we have so many more variables and so many more highs and lows, and you appreciate those highs when you pull off ‘that shot’. The other day I hit a shot that the two-legged version of me couldn’t hit. And it was like, Wow, that was everything. That was just… that’s what you live for.”

Ken continues: “And that’s where you get that extreme desire. It doesn’t matter if you’re missing a leg, or an arm or an eye. Golf will get into your head and once it’s there, you’ve hit the home run, but you’re also going to suffer for the rest of your life because that’s what this game does. What better way to go through life than when you have those highs and lows?”

Competing in G4D events for Ken, or simply playing with golfers who have an impairment, brings pleasure not just from the act of playing but from the people he is meeting on the tee or the club terrace.

“The other great thing about golf and the disabled is that it’s like you become a big family. You become close. People with a disability, they care more about others. I know that sounds awful, but it’s just a fact. They have learned from the disaster of life and they’re going forward, and that’s the one thing I really appreciate, how much everyone really cares about each other.

“I come from that other school so for me, it really surprised me, and one of the first things I noticed is that they genuinely are rooting for each other and they’re proud of them when they pull off a shot. And I’ve been fortunate to play with a couple of seated players, and when they pull off certain shots, it’s like, ‘Wow, that’s incredible’. It gives you chills just thinking about it.”

For his own golf, Ken peppers this interview with the phrase “highs and lows”. The professional game was a tough grind at times but the thrill the game can provide clearly still resonates and remains so important.

“It is. It does. I love golf now as much as I ever did.”

As well as continuing to play Ken is pleased to be able to encourage others to try the game.

“We get personal satisfaction if we play well. But the better part of it is doing interviews like this because of who I used to be. I’m going to get noticed for what I do now. So therefore it is my job to try to get it out there because I’m more apt to be interviewed and the story is more likely to be told because of the fact that I used to be a Tour player, Ryder Cup player and all that kind of stuff. And now I’m a disabled player, so it’s like a Wow to a Wow! And depending on how many people read all these articles… if it helps one or two people, it’s an absolute home run.”

As well as the words “home run”, “love” and “joy” are also much used by Ken, and clearly felt. Ken Green also says “Wow” a lot and he means it, constantly excited by some facet of the game which has sustained him all these years. Surely Ken’s efforts to help others also deserve a Wow! And, Like a ‘gimme’ putt on the course, this word coming from a man who could easily have become so cynical about life, is appreciated every time it is offered.

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions