Apart from carrying the bag and all the measuring and technical analysis, the caddie does so much more. They are a mine of information, the voice of reason, often taken for granted as they walk alongside the player. A witness in time, listening, empathising, learning: with the right inspiration a caddie can change the golf world around them in one shot. Here’s the story of one such caddie, or rather two, both humble bag carriers who have made a significant mark on the game in their own way.

The caddie is an early bird, and is there for you after the last shot.

It’s the start of a golfing day and a tall man walks to the first tee with his caddie. There is the dampness still in the air after the rain, a breeze enough to flap at collars and cuffs. The ground of the teeing area feels firm underfoot. Crows in the tall trees have become quieter as the group of spectators have arrived to watch this match. He is waiting to play. Paul meets the official starter who is clear in his instructions; Paul then swaps his card with his fellow competitor. All the time he is absorbing the facts as he feels them, hears them, while steadying his nerves to hopefully hit a good opening shot.

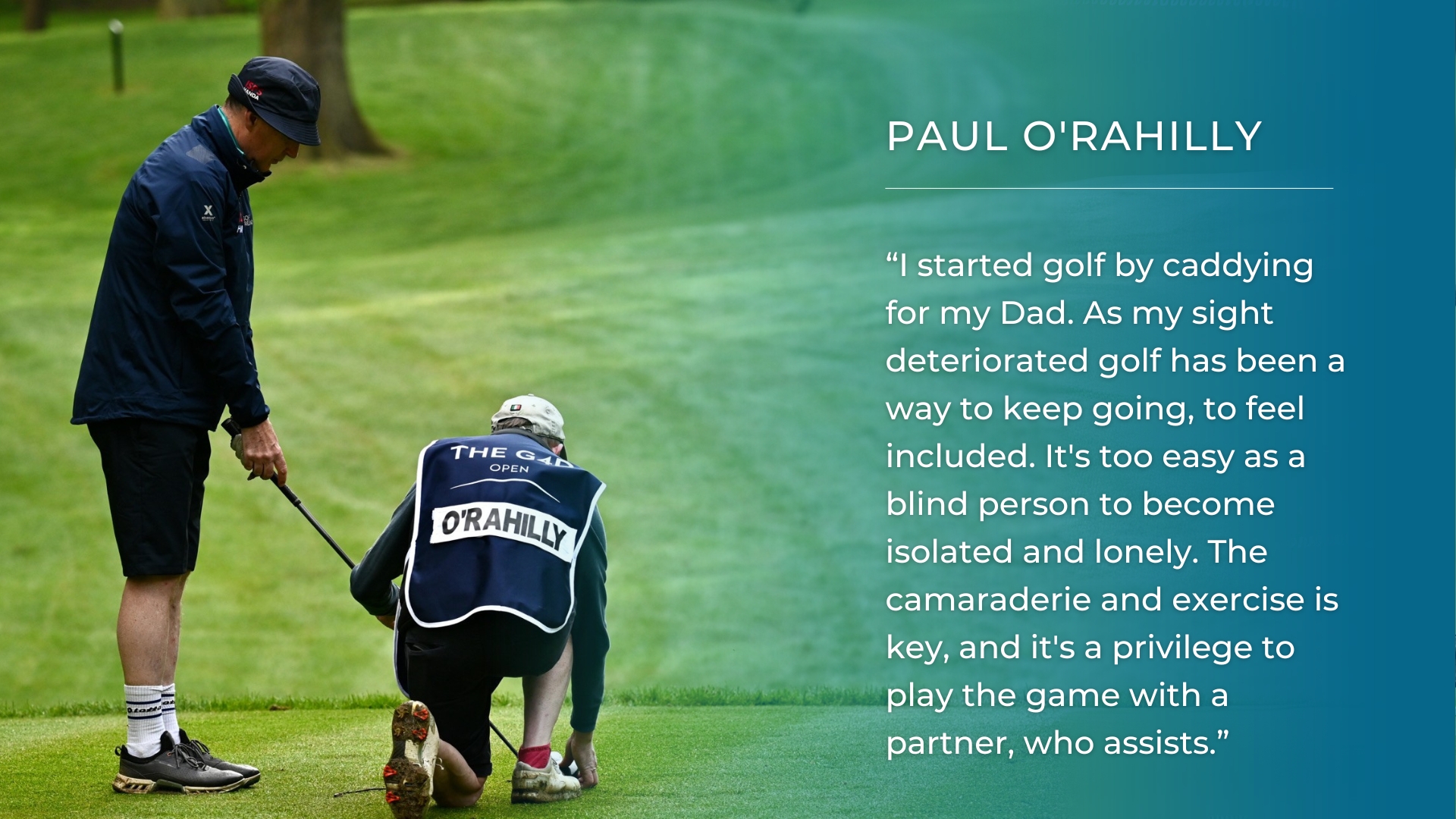

The starter calls out: “On the tee, Paul O’Rahilly, Ireland…” to a smatter of applause. The starter doesn’t add more in description but he could, as also on the tee is John. John is Paul’s caddie and ‘guide’ of 25 years, for O’Rahilly is blind.

John will guide Paul around the course on every shot over undulating terrain. His role is crucial and John is the right person for the job. A unique character and a courageous one, travelling to the event despite having coped recently with a severe illness, there was no way John was going to miss the biggest G4D (golf for the disabled) event Paul has ever qualified for.

The first tee at the Duchess Course, Woburn, heralds one of the most challenging starts in the world of golf. This is The G4D Open, run by The R&A in partnership with the DP World Tour, supported by EDGA. Nine sport classes covering all disability groups; Paul is one of 80 players from 19 countries taking part. There are a few visually impaired players in the field but Paul happens to be the only ‘V1’ golfer present (meaning a player who is towards 100% blind).

To the relief of both men Paul gets his drive away, his tournament has started well. Their tournament has started well.

Paul remembers being a very good player who could see well in his late teens; there is muscle memory and experience there, but the game is a unique challenge for a V1 player. Paul, who lost his sight in stages between 16 and 44, is unfazed by today’s golfing tests and tells us: “I shouldn’t be able to play golf at all, being blind. But, in those rare moments when I make a good strike, execute a birdie or sign for a winning score, I perhaps feel like the deaf Beethoven conducting a great symphony, or the mobility-impaired physicist Stephen Hawking might have felt on writing about the ‘history of time’. It’s moments like these that inspire me to get up in the morning.”

With John ‘on the bag’, this takes Paul back to his own days as a caddie when he could see everything around him just as well as anyone. Back then, the eagle-eyed teenager was guiding players around some beautiful courses in the south east of Ireland in the late 1970s. But as well as sharp eyes, it was also about the ability to listen, to empathise with the player you are working with. Now 61 years-old, he believes he still has the mind of a caddie and now perhaps plays with the combined heart and soul of two people: for Paul and John are a team, shot for shot, step for step. Paul has a vivid memory as a boy caddying for a genuine champion of the game, a golfer who would have a key impact on his thinking about the right and wrong in life, and creating the stoic philosophy he would need to draw upon later to survive and live well.

Not the only deep thinker from County Wexford however. During the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, Wexford was largely a peaceful town in the south of Ireland. However, the divide between Catholics and Protestants was ever present: different churches, schools, friendships and relationships, and even sports (as a Catholic, Paul would play ‘hurling’ but not rugby or cricket).

Paul says: “I recall going to school and listening on the car radio to the stories of the Troubles and war in Vietnam. The world at that stage seemed a very violent place, but I was lucky to live in this quiet little corner. Sport was split along religious lines however, it was also split along gender lines.”

In golf, while girls and women might be playing at the pitch and putt course (very popular in Wexford), at the local golf club social status held sway; businessmen, doctors and lawyers, nearly all male, were teeing it up.

But Wexford itself felt slow, dreamlike amid the hamlets and farms, and it’s no fluke that two of the world’s great writers, John Banville and Colm Toíbín, originated from the area, in the latter’s case Toíbín was brought up only a few miles away from Paul’s house. There’s little doubt they would have passed by each other as youngsters in the coastal village of Blackwater as they were both often there, and there is every chance the poet and writer, perhaps cycling along, may have spied a young lad in his own dream world, throwing a ball against the bricks of the family home.

“I’d throw a tennis ball against the side of the house, and play tennis, hurling, cricket, whatever was on the television; the FA Cup, Wimbledon,” says Paul. “I was out at the ‘gable end’ of the house, reliving the event like many a child does. That’s where I kind of honed my skills for what they’re worth. But a lot of it comes down to having that gable end. That’s the best thing I think you can give a child,” he laughs.

Paul was introduced to golf by his Dad, Gearard (Gerry), and spent “seven years watching, seven learning and seven competing”. The family would move to Dublin when Paul was 10, and a little later father and son started playing together at the famed course The Hermitage near Dublin.

The Irish Dunlop Tournament was staged there in 1978 and young Paul volunteered as a “runner”, tearing back and forth with two copies of each scorecard, running one up to the press room and the other to those operating the large scoreboards. He would meet Irish golfing greats Eamonn Darcy, Christy O’Connor Snr, Des Smyth and others.

But his favourite memory comes from the following year when the European Ladies Team Championship was staged; then he caddied for Catherine Lacoste, the 1967 US Women’s Open Champion, the only Amateur to achieve this honour.

“It was the most wonderful experience and it completely changed my perspective on the game because I was playing it with this lady and she was able to do just about anything with the golf ball. Catherine was driving the ball as far as any man in our club, hitting it a lot more accurately. She was just an astonishing sportswoman. And it completely changed my perspective on the game and who the game was for. Catherine Lacoste left a lasting legacy and influence on many at The Hermitage in her week there.

“I was a teenage boy at the time. The other golfers, the dignitaries, the fans were all following Catherine around as well. Being alongside her gave me confidence. I’ve followed her career since, of course, and she has been inspirational for ladies’ golf in France.”

Young boys can become absorbed in their own little world and it can take a flash of lightning to shake them into thinking differently. Paul will tell you this pairing of caddie and player had such impact. Today, Paul is a great supporter of inclusion and equality in golf, in sport and in wider life. Perhaps also this open-mindedness, the ability to listen and imagine ahead, all reached new heights because of what started to happen next. For only a year after caddying for Catherine, that opportunity in life we all take for granted – to watch, to see the world unfold in front of you at a wonderful time – started to ebb away gradually.

“I was aged 16. I was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) by my local optometrist during a routine sight check. He fixed my astigmatism but couldn’t do a damned thing about the advancing black splodges spreading across my retina.”

Paul kept playing. He would achieve a golf handicap of single-figures by 21. A first clue was when Paul found that his Dad and friends were needed to spot where his (long) drives were finishing. Then, one by one, the challenges arrived for Paul, like men in dark coats. There were “plateaux”. Just as the local literary hero Colm Toíbín went to study at University College Dublin (UCD), Paul also went soon after to study a degree in engineering. Seven years after graduation, he began to experience difficulties in his job, but continued to work as a design engineer and project manager until his sight failed him completely aged 44, in 2008. A career he loved had come to an end.

“I suppose losing your sight is a bit like a death, and you do go through stages of grief. A friend of mine, Michael Griffiths, co-wrote a very good book on this, ‘From Grief to Peace’, and he talks about the different stages of grief and how you experience a parallel to that as you are losing your sight because you lose so much from your life. It’s very gradual and you think, oh God, a couple of years ago I could read a book, a few years before that I could drive. That’s all gone out of my life. But I don’t think you can dwell on that. You have to keep looking forward.

“One of the best bits of advice I got was from an ophthalmologist, a guy called Dr Catford. He said, look, Paul, there’s nothing I can do for you. Science just hasn’t moved on. But you look like the type of guy who’d be able to accept the challenges very well, just see it as a challenge. He just put a thought in my head that stayed with me. So I thought, let’s try and find a new way of doing that. I can’t navigate my studies as quickly as I used to, but I can find a way of getting around that, and you begin to find a new way of doing things.

“It’s like everything in life, you just do it the wrong way first and learn, actually figure out the right way. So you do a lot of silly things when you can’t see, like you’re talking to somebody and they walk away and you don’t know they’ve walked. You end up standing there looking like a fool and talking to yourself; and walking into things and this and that. I think there’s a lot of space left in your brain to use, which you were using to process visual imagery. And I think I use that part to imagine the world that’s around me. So I’m constantly looking for clues, whether they’re audio clues or asking someone what’s there, what’s in front of me? And I will try and build up a picture of what’s there around me.

“While you’re living with a disabling condition you learn other skills. You learn how to socialise, you learn how to get on with people, and that’s so important as you progress in life as well.”

Paul adds: “I brought up my earlier caddying for a reason because I never thought in 1979 that this experience is something I would impart to people caddying and guiding for me when I lost my sight. I know what John is going through as he helps me.”

While we are talking via ‘Zoom’, we are waiting for John to come to Paul’s house so he can discuss how the pair got on at Woburn. John, aged 60, has worked on his family farm since he was 15 (sheep and later cattle) and he still works the farm today. His eventual arrival is somewhat noisy and disruptive as he proceeds to hunt ruthlessly through Paul’s fridge to find a generous snack after coming straight from the field.

Paul merely chuckles amid the noise and goes on to say: “I always appreciate a well designed golf hole as well. Before I go and play a course, I’ll find out which are the feature holes. So I try and get a good picture in my head of those like the 17th at Woburn, it’s an extraordinary golf hole. Very undulating and it’s got that tip in front of the green and the big bunker on the left, and I wanted to know all the information about that hole. And I didn’t take a buggy. I wanted to feel the course under my feet and just feel the clever way in which the hole had been designed and to appreciate that.”

Paul and John describe a ‘mantra’ they term “lie, length and line” that begins with distance of the shot and how the ball lies, above or below the feet, on a slope etc. Then how far to the landing area. “So the shot is forming in my head that I need to play. This is all part of the pre-shot routine and then to choose a club and be ready to hit the ball.” Then John lines Paul up the shot and he swings the club.

“After the shot it’s very important that the guide tells you what has happened. You don’t want to be met with total silence, and have to ask where the ball has gone!” Paul laughs. “You need a description of how the ball flew, did it go high as intended. Did it come out low? Did it check when it hit the green? All of that information I can connect back to how I executed the shot.

“I will hit a rubbish shot, maybe once a hole, I’m afraid. It’s hard to believe, but it does happen,” smiles Paul with his easy humour. “And John’s inclination is to say ‘rubbish shot’, and I say look, what you just said doesn’t help, now just describe what happened because that’s what will help me fix the swing. It also keeps you in a more positive frame of mind as well.”

Like any partnership, after 25 years, familiarity can come into play and Paul accuses John of losing interest when he is playing badly (which now gets a laugh from John). Occasional swearing matches do occur between the two friends. But Paul wouldn’t change it for the world. John was a strong sportsman in his younger days, representing local teams at hurling and soccer, and when Paul still had his sight he took John to the driving range to help him improve his golf. Paul says: “We played together. At that time, I could see the ball on the fairway but needed him to watch the ball for me once it was struck. However, as my sight deteriorated, John played less and caddied more. He got hooked on caddying for me, particularly when we got into position to compete for, and win tournaments. Without John’s friendship and support on and off the course, I simply couldn’t play the game.”

John, himself, is all too modest about his skill as a guide, other than to say how much he enjoys the role. The pair were certainly on form at Woburn and their scoring was a credit to this special partnership.

Paul adds: “John doesn’t think he’s good, but I know he is very good. When I’m playing badly, it’s a challenge to get him to stay focused, but when I’m playing well, he really gets behind me and his enthusiasm to keep me playing well helps me to play even better. Where John is really good, where we’re great in partnership, is from 10 feet; he gives the short putts 110%. And when you’re holing every four-footer on the course and making a lot of six and 10-footers as well, you also relax from tee to green knowing you’re not going to mess things up near the hole. You have that confidence and that’s where John is really, really good.”

What Paul faces alone, like all golfers, is in swinging the club. He works with his coach Eoin O’Connor a lot on a drill for balance and ‘sensory perception’. Eoin will put the ball down and Paul thinks he is addressing the ball in the middle of his stance with a wedge but he’ll be incorrect, and the ball is nearly opposite his right foot, known as false sensory perception. They work on it at the start of every lesson to negate the number of fat and thin shots in practice and play.

The second issue is not being able to see the target. When Paul was 19 and shooting ‘level par nines’, he recalls being “deadly from a hundred yards”, six times out of 10 putting the ball to 15 feet or better. Today, though John is able to line him up so carefully and assess the length of shot, Paul needs a well executed shot to hit the green.

“And I suppose the only difference when you’re blind is having the confidence to know that what you’re feeling at the different points in the swing – from your grip pressure to your takeaway to what you do to initiate the downswing; to the acceleration and the low follow-through – the golf swing is so fast that once you’re set up properly, any golfer should be able to just close their eyes and hit the ball. It’s surely just muscle memory at that point.”

While Eoin enjoys the challenge of coaching Paul in a different way, Paul relishes being able to share his experiences to help other people with a disability, which includes running sessions for youngsters at his club, some of whom are visually impaired. Paul says these sessions, supported so well by the members at his club, Gowran Park, a short distance from the city of Kilkenny, are proving fantastic for the youngsters. Just as Paul was inspired to open his mind to think about the value of inclusion, by Catherine Lacoste and others and from studying his community around him, he is now helping to inspire others.

“There is also a huge added benefit for the parents and families getting together, so that the children and parents are all extending their social circle, and you can imagine how good that can be for families who have to face the hurdles of disability, sometimes feeling as if they are on their own.”

Paul describes his recent experiences of travelling to Thailand and Costa Rica with The R&A to play tournaments and support local people with sight loss as “a fantastic honour”. He has regularly teamed up with Golf Ireland on successful inclusive projects and he chairs a WhatsApp group for ‘V1’ players, highly visually impaired golfers, in which he is collating opinion and feedback on their experiences playing the game, to share with the research team at EDGA. Paul has also helped raise awareness for G4D by taking part in events organised by RSM.

These contributions have clearly helped shape his identity as a golfer and man. Not as a victim of circumstance, but as a strong competitor and a golfer with whom you will want to share a fairway. But it is more than that. Talking with him, Paul clearly has an extended capacity to listen and process information to help others. He defines the benefits of golf for him in simple terms.

“I started golf by caddying for my Dad. As my sight deteriorated golf has been a way to keep going, to feel included. It’s too easy as a blind person to become isolated and lonely. The camaraderie and exercise is key, and it’s a privilege to play the game with a partner, who assists.”

Golfers often cite another player who has inspired them, and Paul could list a cast of figures who have galvanised his mind to cope with sight loss, including his Dad Gerry’s encouragement, and in a huge way from John his guide and friend, from Dr Catford’s careful, elegant words of wisdom, and then of course there is Catherine Lacoste.

Catherine would have been inspired to play by her mother, the fine golfer Simone Thion de la Chaume (British Ladies Amateur Champion, 1927), and her father René Lacoste, who, when he wasn’t winning seven Grand Slam tennis titles and being later celebrated in crocodile badged tennis shirts, was a good six-handicap golfer himself. During our chat, Paul, an intelligent and shrewd follower of history, describes both Catherine Lacoste and Wexford’s local world-famous writer Colm Toíbín as “true trailblazers”. Catherine would no doubt agree that her 15-year-old caddie at The Hermitage circa 1979 has become a genuine trailblazer himself. And Paul, being Paul, would not forget the support of his own caddie John for a second.

– The G4D Open (May 15-17) takes place at Woburn, near Milton Keynes, with free entry for spectators.

NB: When using any EDGA media, please comply with our copyright conditions